AMQP Broker

This was an exercise of the Network Programming subject that I attended during the first semester of my master’s course. I was really happy with the result, so I thought it is worth to be mentioned here.

The idea was to create a server written in C that should interpret and process AMQP messages, used by message brokers such as RabbitMQ. Encryption and fail tolerance wasn’t required, so, I didn’t implemented that. This means that this code is a toy, and it isn’t suitable for real-life purposes.

As technical requirements, it had to:

- be compatible with AMQP 0.9.1;

- be able to accept connections and disconnections of clients;

- declare queues;

- accept connections of several clients at the same time;

- allow clients to subscribe a queue;

- allow clients to push a message to a queue;

- only use ASCII characters;

- work on GNU/Linux;

The code is available on GitHub. You can find instructions on its README.

Development

This code was written based on the AMQP specification. In addition, I observed the message exchange between the clients and the server using Wireshark, so, this was partially developed by reverse-engineering RabbitMQ.

I used as clients the command line tools suit amqp-tools, available on the

repositories of most Linux distributions and on Homebrew.

Detailed design

Data structures

Queues

The queues were defined as linked lists. These are their nodes:

typedef struct q_node {

struct q_node *parent;

int length;

char body[1];

} q_node;

Note that the last field (the body of message in a queue) is a char array with

only one element. This is because this linked list node is also a

flexible array.

This is a technique to dynamically allocate an array in C and other fields (in this case,

the pointer to the next node and the length of the body) in a single call, like

this:

q_node *n;

int length = strlen(body);

n = malloc(sizeof(*n) + length * sizeof(char));

n->parent = NULL;

n->length = length;

strcpy(n->body, body);

Here, malloc allocates enough size to the struct fields and the

number of characters of the string body. The byte used for the null terminator

is already in the struct (the 1 in body[1]).

Tries

Tries are a data structure that I always found very elegant but I have never had a use case that I need them. So, this was the first time that I implemented one.

Oh, and if you don’t know what a trie is, you can read about it on Wikipedia. They are trees used to build symbol tables where the keys are strings. Each character of the string is a node, and the node of the last character references the value.

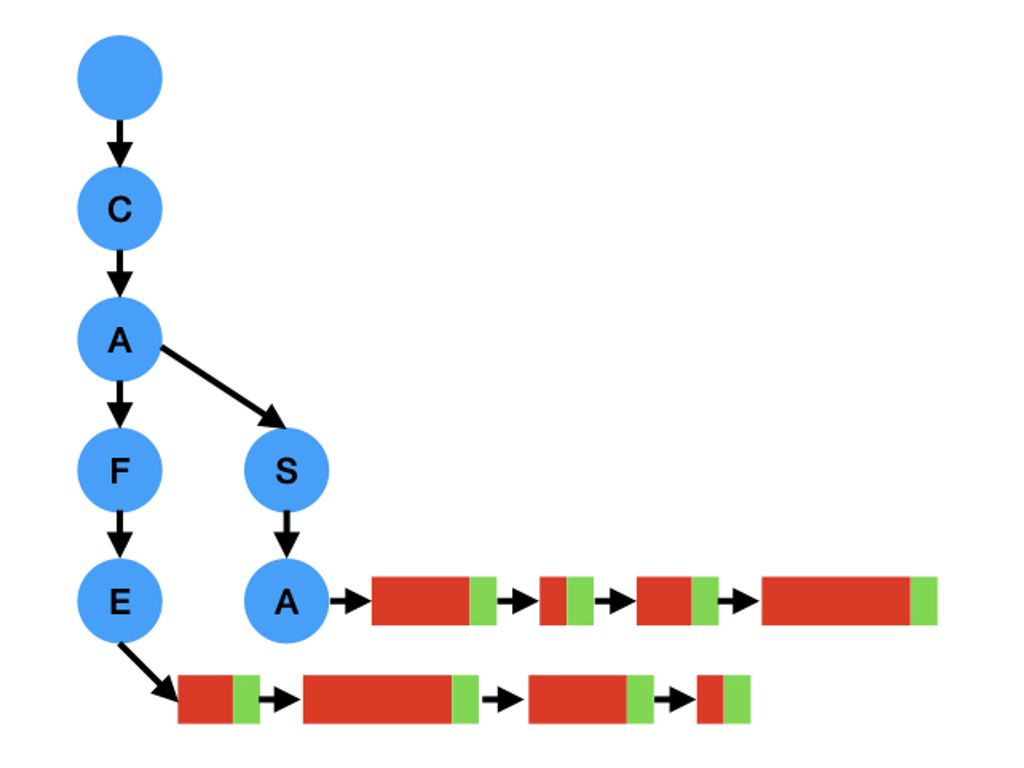

I used tries to index the queues by their names. In the following picture, I

have two queues named CAFE and CASA (the Portuguese words for “coffee” and

“house”). The trie nodes are in blue, the fixed portion of the queue nodes are

in green and the flexible portion of the queue nodes are in red:

These two data structure are the only ones that I’m dynamically

allocating. I’m avoiding mallocs in this code, so I don’t need to care too

much about memory leaks.

Messages

Writing a code in C has its advantages, mainly because of it being in a lower

level compared to most of the other high-level languages. One thing that it

helped a lot here is that I didn’t need write a complex parser to read AMQP

messages. The AMQP protocol defines fixed-length fields, that can be represented

as fields in a struct in C. This means that, for most cases, it was enough to

declare the structure, as I did here:

/* Message header. The header of an amqp message (except protocol header). */

typedef struct {

uint8_t msg_type;

uint16_t channel;

uint32_t length;

} __attribute__((packed)) amqp_message_header;

And after that, the raw data could be directly copied to the memory address of that struct, and converting the endianness of the fields:

static int parse_message_header(char *s, size_t n, amqp_message_header *header) {

size_t header_size = sizeof(amqp_message_header);

if (n < header_size) return 1;

memcpy(header, s, header_size);

header->channel = ntohs(header->channel);

header->length = ntohl(header->length);

return 0;

}

If you are curious about what __attribute__((packed)) means, it is needed to

avoid padding.

State machine

This was mostly copied from the README. Sorry for the ASCII diagrams, but the README was written to be displayed in a terminal, and would take too much time remaking them in SVG, so I kept them as they were.

AMQP is a stateful protocol, so it’s natural that we keep the connection control using a state machine.

Each state machine is created after the beginning of the connection with the client, starting in the state WAIT. In that state, it waits for the protocol header.

The last state of the connection is FINISHED, when the connection finishes gracefully. There is also a FAIL state, if something goes wrong.

State machine diagram

The FAIL stated is hidden here in order to simplify the diagram, as any state may have a event that leads to it.

The connection establishment states are the following:

*--------* *------------* *------------*

| WAIT | -------------------> | HEADER | --------> | WAIT |

| | C: Protocol Header | RECEIVED | S: Start | START OK |

*--------* *------------* *------------*

|

C: Start OK |

|

*-----------------* *-----------* *------------* |

| WAIT |<---------- | WAIT | <-------- | START OK | <--

| OPEN CONNECTION | C: Tune Ok | TUNE OK | S: Tune | RECEIVED |

*-----------------* *-----------* *------------*

|

| C: Open Connection

|

| *-----------------* *-----------------*

--> | OPEN CONNECTION | ----------------------> | OPEN CONNECTION |

| RECEIVED | S: Open Connection OK | RECEIVED |

*-----------------* *-----------------*

|

C: Open Channel |

|

*-------------* *--------------* |

| WAIT | <--------------------- | OPEN CHANNEL | <---

| FUNCTIONAL | S: Open Channel OK | RECEIVED |

*-------------* *--------------*

|

| C: Method

|

|-> Queue declare states

|

|-> Publish states

|

-> Consume states

After the state WAIT FUNCTIONAL, it can close the connection, or take one of these different paths:

- queue declare

- publish

- consume

Each one of them can begin the connection closing in its states. This will also be hidden here in order to simplify the diagram.

The queue declaration states are the following:

*------------* *---------------*

| WAIT | -------------------> | QUEUE DECLARE |

| FUNCTIONAL | C: Queue Declare | RECEIVED |

| | | |

| | <------------------ | |

| | S: Queue Declare OK | |

*------------* *---------------*

The publish states are the following:

*------------* *---------------* *----------------*

| WAIT | -------------------> | BASIC PUBLISH | -> | WAIT PUBLISH |

| FUNCTIONAL | C: Basic Publish | RECEIVED | | CONTENT HEADER |

*------------* *---------------* *----------------*

^ |

C: Basic Publish | C: Content Header |

| |

| *----------------* |

|-------- | WAIT PUBLISH | <-

| | CONTENT |

-------> | |

C: Body | |

*----------------*

The consume states are the following:

*------------* *---------------*

| WAIT | ----------------> | BASIC CONSUME |

| FUNCTIONAL | C: Basic Consume | RECEIVED |

*------------* *---------------*

|

| S: Basic Consume OK *------------*

---------------------> | WAIT VALUE |

-----------------------------------------> | DEQUEUE |

| C: Consume Ack *------------*

| |

| |

| Q: Dequeue |

| |

*--------------* *---------------* |

| WAIT CONSUME | <------------------- | VALUE DEQUEUE | <--

| ACK | S: Basic Deliver | RECEIVED |

| | S: Content Header | |

| | S: Body | |

*--------------* *---------------*

The connection close can be started on several states when they receive close channel or close connection messages:

*---------------* *-----------*

----------------> | CLOSE CHANNEL | -------------------> | WAIT OPEN |

C: Close Channel | RECEIVED | S: Close Channel OK | CHANNEL |

*---------------* *-----------*

*------------------* *----------*

-------------------> | CLOSE CONNECTION | ----------------------> | FINISHED |

C: Close Connection | RECEIVED | S: Close Connection OK | |

*------------------* *--------- *

Experiments

Performance analysis was part of the exercise, and I think it’s cool to show it here only as a matter of curiosity. I don’t want to be too much scientific here.

Setup

This setup was composed by old single-board computers (two Beaglebones and one Raspberry Pi) named Emerson, Lake and Palmer (I consider yourself my friend if you know who are them), my old laptop (name Wall-e), and an old Linksys WRT54G router.

My new laptop (named Eve, yeah, just because the older one is Wall-e) was not part of the experiment because it is too powerful and I wanted to see it running on weak machines, however, I used it to remote access them.

Here’s their specs and roles:

| Machine | CPU | Number of Cores | RAM | OS | Connection Type | Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wall-e | Intel core i5 | 2 | 8GB | Manjaro Linux | Wired | Server |

| Eve | Apple M1 | 8 | 8GB | Mac OS Monterey | WiFi | Remote access |

| Emerson | ARM Cortex A8 | 1 | 230MB | Debian Buster | Wired | Publisher |

| Lake | ARM Cortex A8 | 1 | 484MB | Debian Buster | Wired | Publisher |

| Palmer | BCM2835 | 1 | 432MB | Debian Bullseye | Wired | Consumer |

And about the network, iperf show us that the network throughput between

Emerson and Wall-e and Lake and Wall-e was about 94 Mb/s and between Palmer and

Wall-e was about 53Mb/s.

Observations

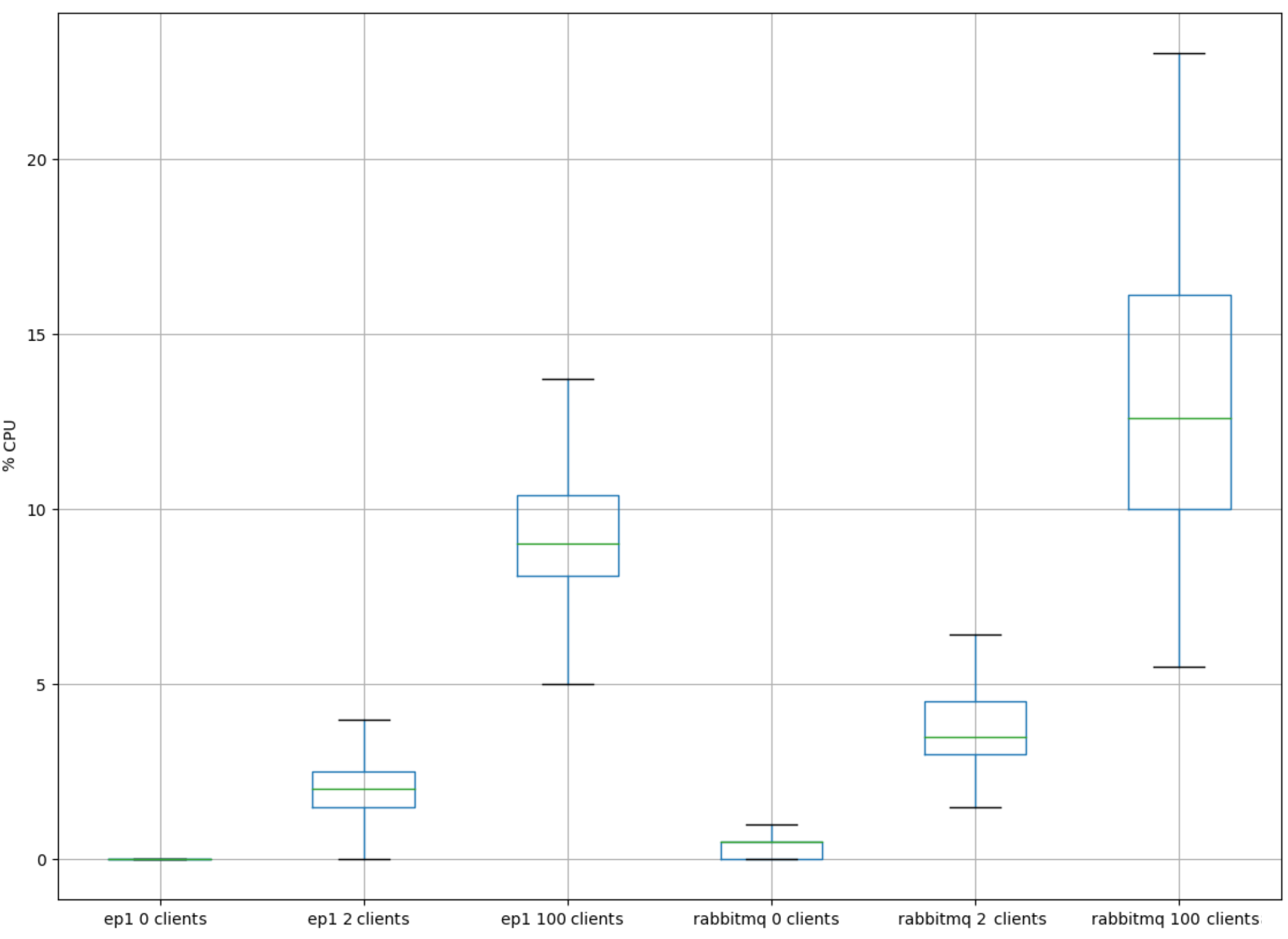

CPU

Comparing the CPU usage of this AMQP server and RabbitMQ, we can see that this performed slightly better for 0, 2 and 100 clients connected (the server developed here denoted by “ep1” in all the graphics).

Network

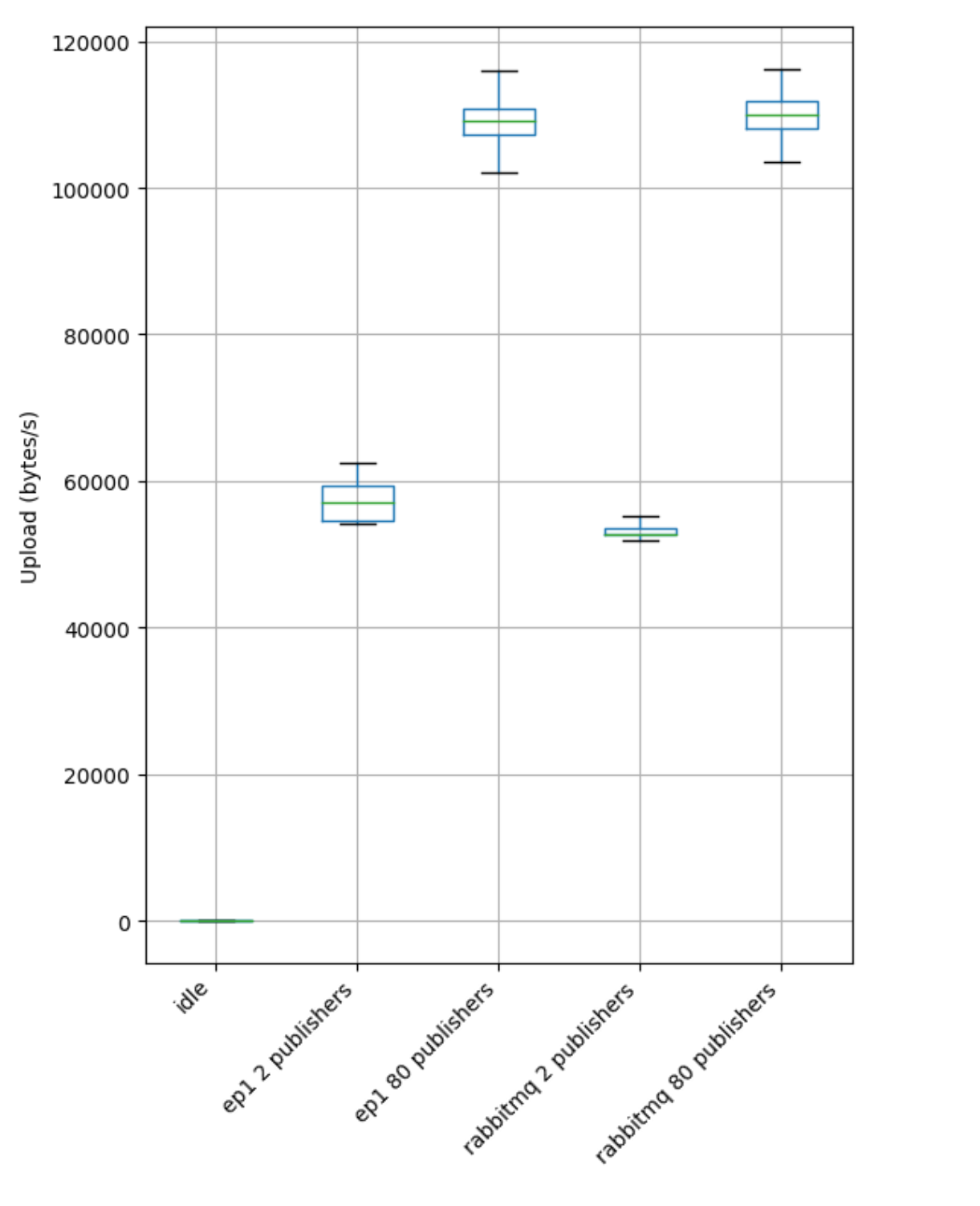

Comparing the upload rate of a publisher machine between both servers, they are basically the same:

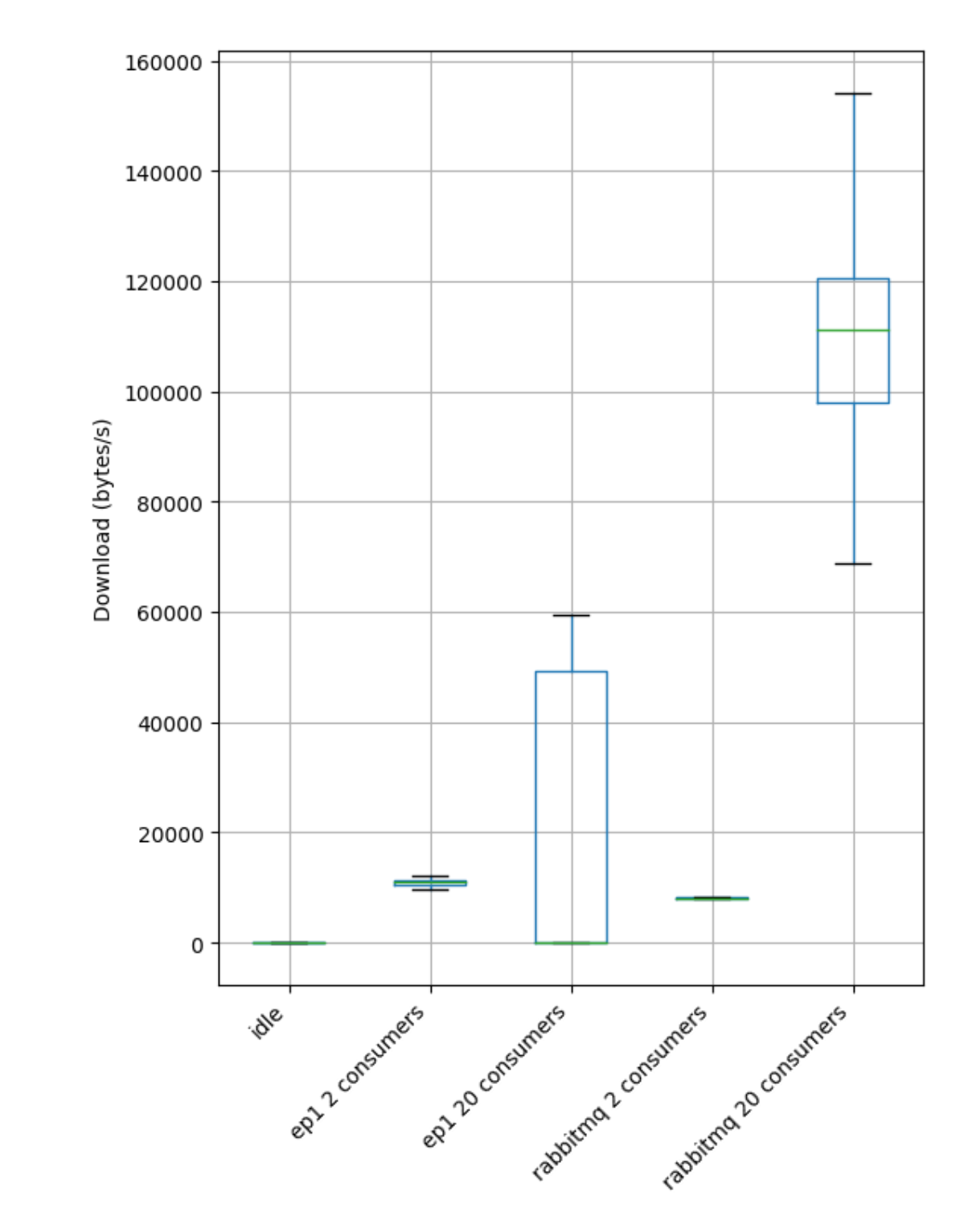

Comparing the download rate of the consumer machine, we can see that RabbitMQ provided more data per second:

RabbitMQ is the winner here!

Conclusion

This was a really hard exercise, and it demanded a lot of time to understand the protocol, to develop and to experiment. But sincerely, I like this kind of thing that reinvents the wheel because it makes me learn more deeply about how things work. I have never used RabbitMQ directly before, and everything is now clear to understand since I have an idea of what’s under the hood.

If you are thinking that the performance was too good to a toy project developed by just one person, keep in mind that this is extremely simple compared to the real RabbitMQ. A lot of features of RabbitMQ (for example, channels, exchanges, encryption, authentication) are missing.

Also remember that RabbitMQ runs on the Erlang virtual machine while this is compiled to a native binary, so, it’s expected to use less resources when there’s low demand. However, it doesn’t mean that it is performing better, as you could see RabbitMQ could deliver more data per second compared to this one.